|

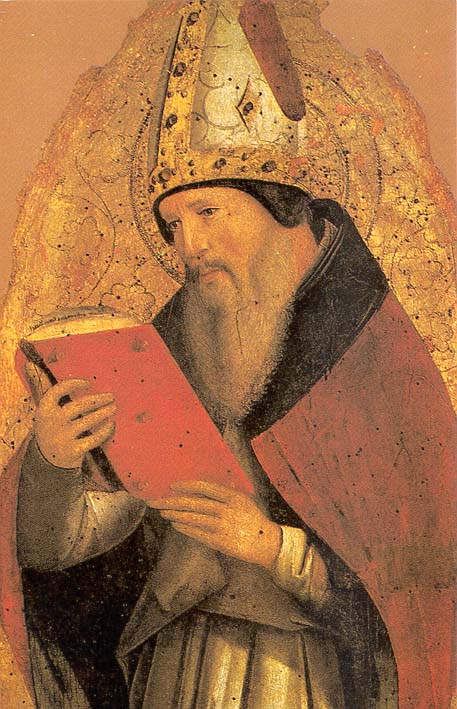

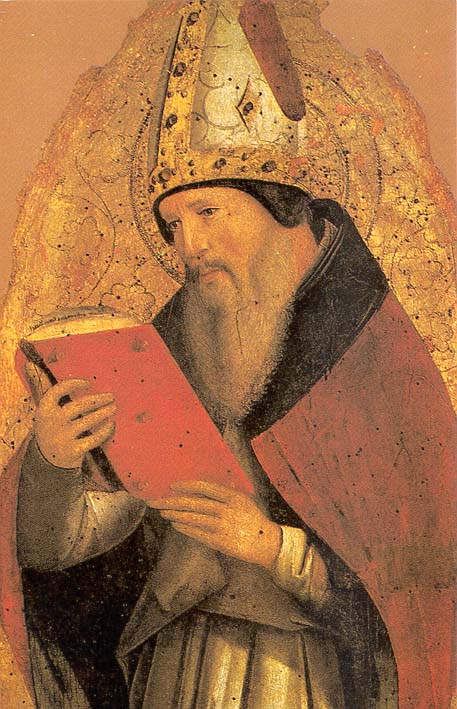

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 A.D.)

Saint Augustine made no

secret of his admiration for Plato; In his work entitled The City of God

(Book 8), Augustine wrote:

Among the disciples

of Socrates, Plato

was the one who shone with a

glory which far

excelled that of the others, and who not

unjustly eclipsed

them all. ... For those who are praised as having most closely followed

Plato, who is

justly preferred to

all the other philosophers of the Gentiles ... Of which three things, the first is understood to pertain

to the natural, the second to the rational, and the third to the moral part

of philosophy. For

if man has been so created as to attain, through that which is most

excellent in him, to that which excels all things,—that is, to the one

true and absolutely

good God, without

whom no nature exists, no doctrine instructs, no exercise profits,—let Him

be sought in whom all things are secure to us, let Him be discovered in whom

all truth becomes

certain to us, let Him be loved in whom all becomes right to us. ...

... It is evident that none come nearer to us than the

Platonists. ... The

Platonic

philosophers ... have recognized the

true God as the author of all things, the source of the light of

truth, and the

bountiful bestower of all blessedness. And not these only, but to these

great acknowledgers of so great a

God, those

philosophers must

yield who, having their mind enslaved to their body, supposed the principles

of all things to be material; as Thales, who held that the first principle

of all things was water; Anaximenes, that it was air; the

Stoics, that it was

fire;

Epicurus, who

affirmed that it consisted of atoms, that is to say, of minute corpuscles;

and many others whom it is needless to enumerate, but who

believed that

bodies, simple or compound, animate or inanimate, but nevertheless bodies,

were the

cause and

principle of all things. ...

... Whatever

philosophers,

therefore, thought concerning the supreme

God, that He is

both the maker of all

created things, the light by which things are

known, and the good

in reference to which things are to be done; that we have in Him the first

principle of nature, the

truth of doctrine,

and the happiness

of life,—whether these

philosophers may be more suitably called Platonists, or whether they may

give some other name to their

sect; whether, we

say, that only the chief men of the Ionic school, such as

Plato himself, and

they who have well understood him, have thought thus; or whether we also

include the Italic school, on account of Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans,

and all who may have held like opinions; and, lastly, whether also we

include all who have been held wise men and

philosophers among

all nations who are discovered to have seen and taught this, be they

Atlantics, Libyans, Egyptians, Indians, Persians, Chaldeans, Scythians,

Gauls, Spaniards, or of other nations,—we prefer these to all other philosophers, and

confess that they approach nearest to us. ...

... Certain partakers with us in the

grace of

Christ, wonder when

they hear and read that

Plato had conceptions concerning

God, in which they

recognize considerable agreement with the

truth of our

religion. ... What

warrants this supposition are the opening

verses of Genesis: "In the beginning God made the heaven

and earth. And the earth was invisible, and without order; and darkness was

over the abyss: and the

Spirit of God moved

over the waters."

[Genesis 1:1-2 ]

For in the Timćus, when writing on the formation of the world, he

says that God first united earth and fire; from which it is evident that he

assigns to fire a place in heaven. This opinion bears a certain resemblance

to the statement, "In the beginning God made heaven and

earth."

Plato next speaks

of those two intermediary elements, water and air, by which the other two

extremes, namely, earth and fire, were mutually united; from which

circumstance he is thought to have so understood the words, "The

Spirit of God moved

over the waters." For, not paying sufficient attention

to the designations given by those scriptures to the

Spirit of God, he

may have thought that the four elements are spoken of in that place, because

the air also is called spirit. Then,

as to Plato's

saying that the

philosopher is a lover of

God, nothing shines

forth more conspicuously in those sacred writings.

Thus, the

greatest of the Church Fathers marvels that the belief system espoused by Plato

and certain other Greek philosophers was so closely aligned with Christian

beliefs. In my view, this similarity is to be expected. Augustine seems

not to have recognized the strong possibility that the influx of so many

Hellenized Jews and Greek speaking gentiles during the period from the late first century

through the third century A.D. may have gradually altered Christian beliefs to

be consistent with the prevailing Greek philosophical ideas of that timeframe.

|