Close Friends of Giorgio

de Santillana

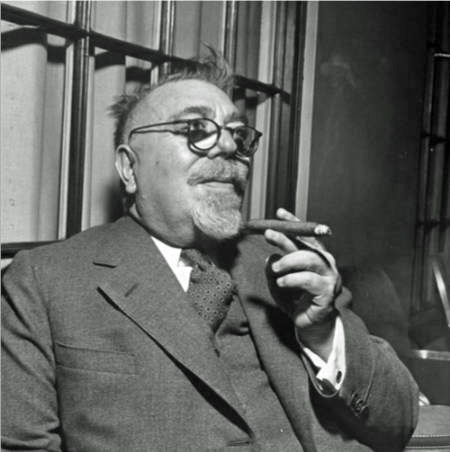

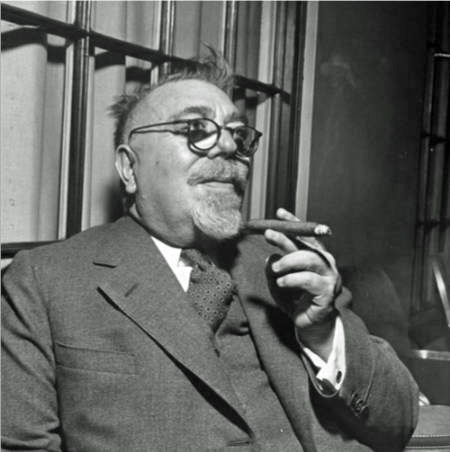

Norbert Wiener (1894-1964) |

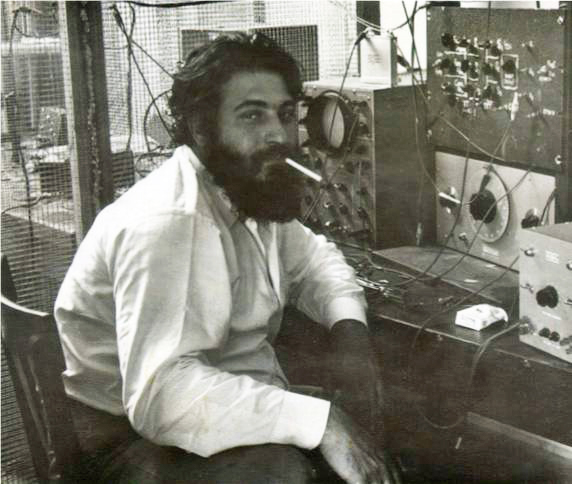

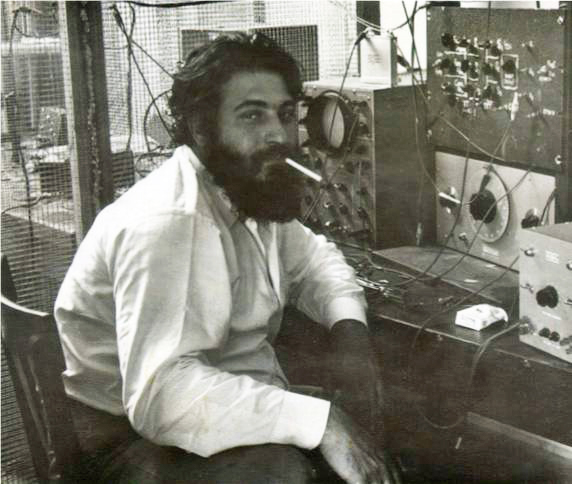

Jerome Lettvin (born 1920) |

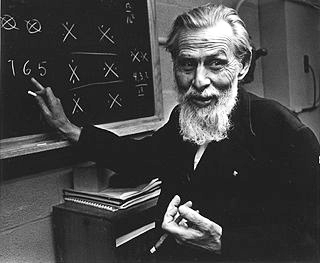

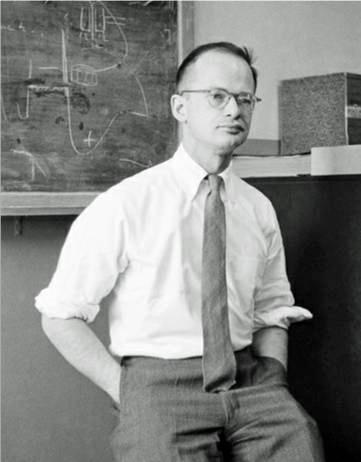

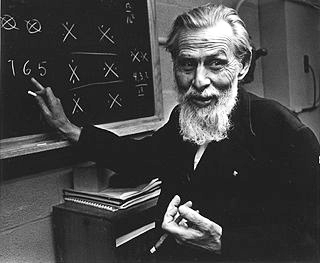

Warren McCulloch

(1898-1969) |

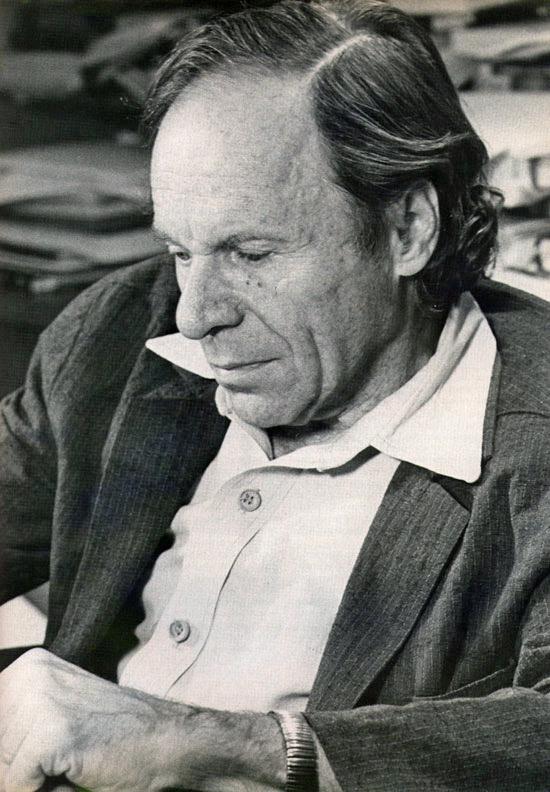

Philip Morrison

(1915-2005) |

Walter Pitts (1923-1969) |

The five gentlemen whose photographs

appear above were all good friends of Giorgio de Santillana and of each

other.

1)

Norbert

Wiener

was a child prodigy; in 1913, he acquired a Ph.d. from Harvard in

mathematics at only 18 years of age.

In 1919, he joined the faculty of MIT, becoming

a full professor of mathematics in 1931. During World War II, his work on

the automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns caused Wiener to study

Communication

Theory and eventually formulate his theory of

Cybernetics in 1948.

After the war, his fame enabled MIT to recruit a research team in

Cognitive Science,

composed of researchers in neuropsychology, mathematics and biophysics of

the nervous system; these researchers included Warren McCulloch and Walter

Pitts. All of these men later made pioneering contributions to Computer

Science and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Wiener and Giorgio de Santillana were close

friends at MIT during the 1940s and 1950s, until Norbert's retirement in

1960. They enjoyed discussing topics related to the philosophy of science

and mathematics with each other. On a lighter note, Giorgio was an expert on

Tarot card reading and Wiener loved to have his fortune told.

2)

Jerome Lettvin

was a cognitive scientist and Professor of Electrical

and Bioengineering and Communications Physiology at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is best known as the

principal author of the 1959 paper: "What the frog's eye tells the frog's

brain" - one of the most cited papers in the

Science Citation Index. He wrote the paper with the assistance of

Humberto Maturana,

Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts. A graduate of the University of Illinois

Medical School, Lettvin practiced Psychiatry in Illinois and later in

Boston. In 1951, at the urging of Norbert Wiener, both Lettvin and Warren

McCulloch, joined the faculty at MIT.

Through their association with Norbert

Wiener, both Lettvin and Warren McCulloch met and became a close friends of

Giorgio de Santillana. Lettvin had the following reminiscence concerning

Giorgio de Santillana and Norbert Wiener:

One of my best friends at MIT was

Giorgio de Santillana, the historian of ideas. He was a most learned and

kindly man with a mordant wit. Walter, Wiener, and I often hung out at his

office. Giorgio was a past-master at fortune-telling with the Tarot. Wiener

loved having his fortune told. Giorgio vainly tried to persuade him that the

Tarot should be a rare and sometime thing to be used only in crisis, but

Wiener would have none of such excuses. For example, Walter and I used it

when we started a new experimental venture. There's nothing mystical about

it - it brings up, by chance, associations that you do not ordinarily

consider and in that way serves to break the constraints that hemmed your

thinking. It is a charming way of introducing overlooked contingencies. So

every month or so, Giorgio would give in to Wiener and come up with a

fortune together with a complex character analysis. At the end of the

reading, Wiener would exclaim "But that's not me, that's X (or Y or Z)"

where X, Y, or Z were fellow mathematicians. Giorgio would shrug and say

"You may have been thinking of them when you picked the card."

-- The History of Neuroscience in

Autobiography, Volume 2 (published 1998), Edited by Larry R. Squire,

pages 234-235.

In an

interview given in 1994, Jerry Lettvin told the story of the time

that de Santillana read the Tarot for Lettvin's wife Maggie:

Let me describe Maggie for you. She

was one of the most beautiful women I ever met, in both appearance and

character, utterly unpretentious and with great native intelligence. My

family looked down on her, my friends did not. She had had only a high

school education, and my mother stayed angry for years.

One evening, shortly after we came to

MIT, we visited Giorgio de Santillana, the historian of ideas and an old

friend from my student days, at MIT. Giorgio was an adept at interpreting

the Tarot. Scarcely a month would go by but Wiener would insist on having

his Tarot told. Giorgio vainly explained that the Tarot should be consulted

only at times of important choice. Wiener claimed he always had such a

crisis and needed counsel. At any rate Giorgio was charmed by Maggie and

offered to read the Tarot for her. She was now about twenty-five. He read

the cards with a faint air of disbelief. They told that by age forty she

would become a figure of renown, an author and an innovator. Maggie still

remembers that evening with some awe, for all came true.

In her early thirties, after we had

forged our three kids she was back-ended by a hit-and-run driver. For months

she could scarcely lift here arms. Refusing surgery, she studied Gray's

Anatomy and worked out what sort of mechanical regimen would restore her.

Recovery was slow but steady, and within a year she was symptom-free. Others

came to her for their mechanical disabilities and she worked out from here

newly gained knowledge of anatomy and kinematics some remarkably successful

conservative treatment. She charged nothing, was only interested in helping.

Several students, after being helped, persuaded her to hold fitness classes

at MIT. Within a year there were about two hundred people per day taking

those classes. Then Channel 4 in Boston picked her up, then PBS. For the

next seventeen years her program, Maggie and the Beautiful Machine

(everybody's body), was a PBS standby and her MIT classes stayed crowded.

She published four books in her forty's and gloried in the fact that medical

practitioners approved of her approach. One book is still in print after

twenty-five years. Now she is beginning a new career on the Web, giving

counsel on how to relieve back pain without medicaments.

The only pity is that Giorgio could

not know that all this happened. He began failing before her ascent picked

up steam.

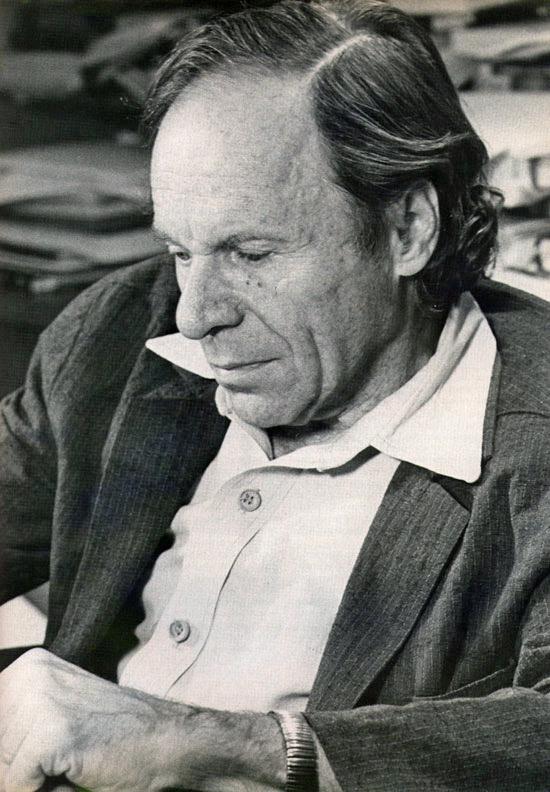

3)

Warren

McCulloch was a Neurophysiologist and

Cybernetician. His work helped to establish the Neural Network theory of the

brain in a number of classic papers: including "A Logical Calculus of the

Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity" (1943) and "How We Know Universals: The

Perception of Auditory and Visual Forms" (1947). From 1952 he worked at the

MIT Research Laboratory of Electronics, working primarily on neural network

modeling. His team examined the visual system of the frog in consideration

of McCulloch's 1947 paper, discovering that the eye provides the brain with

information that is already, to a degree, organized and interpreted, instead

of simply transmitting an image. The result of that research was summarized

in the paper he authored with Jerome Lettvin,

Humberto Maturana

and Walter Pitts entitled: "What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain"

(1959).

4)

Philip Morrison

was a theoretical physicist and astrophysicist. In

1940, he earned his Ph.D. in theoretical physics at the University of

California, Berkeley, under the supervision of

J. Robert

Oppenheimer. In 1942 he joined the

Manhattan Project

as group leader and physicist at the laboratories of the University of

Chicago and Los Alamos. In July 1945, he was an eyewitness to the

Trinity Atomic Bomb test and helped to transport its plutonium core to

the test site. From 1946 until 1964, Morrison was on the faculty of Cornell

University working primarily in the field of theoretical astrophysics. In

1964 he joined the MIT faculty as a professor of Physics, becoming an

Institute Professor in 1973.

After coming to MIT, Philip Morrison became a

good friend of Giorgio De Santillana. When Giorgio's last book was

published, Hamlet's Mill, Morrison did a book review that was

published in the November 1969 issue of Scientific American. It was

one of the few sympathetic reviews made of that book by academics. Morrison

made this summary statement concerning the book:

The book is polemic, even cocky; it

will make a tempest in the inkpots. It nonetheless has the ring of noble

metal, although it is only a bent key to the first of many gates.

5)

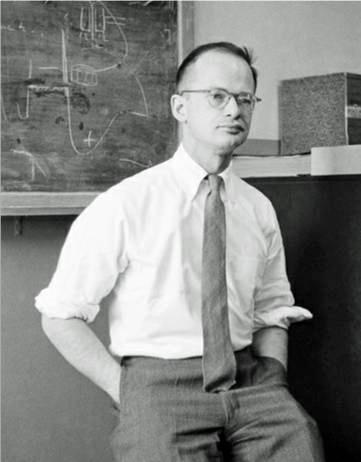

Walter Pitts

was an

autodidact who basically taught himself

logic and mathematics; he was also able to read a fair number of languages,

including Greek and Latin. Like Norbert Wiener, he was a childhood prodigy

and a genius of the highest order. At the age of 12, he spent three days in

a library reading

Principia

Mathematica and sent a letter to

Bertrand Russell

at Cambridge University pointing out what he considered to be serious

problems with the first volume. Russell was appreciative and invited him to

study in England. Although this offer was not taken up, Pitts decided to

become a logician. In 1938, Pitts ran away from home at the age of 15 to

attend Russell's lectures at the

University of

Chicago. He stayed there attending lectures, without registering as a

student. While at Chicago in 1938, he met Jerome Lettvin, who was actually a

registered student there, and the two became good friends. Pitts also met

the logician Rudolf

Carnap at Chicago by walking into his office and presenting him with an

annotated copy of Carnap's recent book on logic. Carnap was so impressed by

Pitt's understanding of advanced logic that he arranged for Pitts to be

given a menial job at the university. Pitts at that time was homeless and

without income.

Later Warren McCulloch arrived at the University of

Chicago; in early 1942, he invited Pitts, who was still homeless,

and Jerome Lettvin to live with his family. In the evenings

McCulloch and Pitts discussed many topics of mutual interest. Pitts

was familiar with the work of the 17th century philosopher

Gottfried

Leibniz on computing and they considered the question of whether

the nervous system could be considered a kind of universal computing

device as described by Leibniz. This led to their seminal paper: "A

Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity" (1943). This

paper proposed the first mathematical model of a Neural Network. The

unit of this model, a simple formalized neuron, is still the

standard of reference in the field of neural networks. It is often

called a

McCulloch–Pitts Neuron.In 1943, Jerry

Lettvin introduced Pitts to the mathematician Norbert Wiener, who

was in need of an assistant. Their first meeting went so well that

Pitts moved to Cambridge to work with Wiener at MIT. While at MIT,

in 1951,

Walter collaborated with Giorgio

de Santillana in writing an

article entitled: "Philolaus in Limbo: or,

What happened to the

Pythagoreans" for Isis, the

academic journal for the history of science. Also in 1951, Norbert

Wiener convinced MIT to establish a brain research group composed of

mathematicians and physiologists of the nervous system. This group

included Pitts, Lettvin and McCulloch. Pitts wrote a lengthy thesis

on the properties of neural nets connected in three dimensions.

Jerry Lettvin described Pitts as being "in no uncertain sense the

genius of the group … when you asked him a question, you would get

back a whole textbook."

Although a genius, Pitts was also an eccentric and

very private person. He refused all offers of advanced degrees or

official positions at MIT because his name would then become known

to the public. Pitts was devoted to the pure and total life of the

mind, believing it to be superior to a life of more complicated

relationships with people. During the 1960s, he became increasingly

withdrawn and more exclusively attached to Warren McCulloch.

Perhaps he sensed that, in some collaborations with other people, he

was being used. Several of the scientists and psychiatrists of the

brain research group thought that Pitts was schizophrenic and

potentially very ill. The prominent psychiatrists who moved in his

circles were more and more baffled by his reclusive shyness and his

apparent personal discomfort. Later Pitts began to live on his own

in Cambridge where he may have experimented with homemade drugs. No

one seems to know much about his later life. He died in 1969 and

there is speculation that he committed suicide.

Dorothy de Santillana (1904-1980)

- Wife of Giorgio

Actress Helen Coxe (shown above) plays

Dorothy de Santillana in the 2009 film Julie & Julia.

Professor de Santillana's wife, Dorothy, is

at least as famous and perhaps more famous than her distinguished husband.

Her full maiden name is Dorothy Hancock Tilton; she was the daughter of John

Hancock Tilton and Elizabeth Worthington Seeley. The Tilton family of

Massachusetts enjoys a very distinguished New England lineage; indeed,

Dorothy is a direct descendent of John Hancock (1737-1793), first signer of

the Declaration of Independence! I have added a separate page to this

website devoted to the Tilton Family

Genealogy.

Dorothy was born on 23 August 1904 in Essex

County, Massachusetts; she died on 19 June 1980 in Beverly, Massachusetts.

Her father, John Hancock Tilton (born on 16 September 1870), was a

successful real estate and insurance broker; Dorothy grew up in a

comfortable upper middle class environment in Haverhill City, a northern

suburb of Boston. Dorothy was a graduate of

Radcliffe College

(the women's liberal arts college affiliated with Harvard University), where

she met and married the noted poet

Robert Hillyer

(1895-1961) in 1926. In the 1930 Federal Census, Dorothy, Robert and their

two-year-old son Stanley (1927-1969), are listed in the enumeration for

Windham County, Connecticut; both were identified as being teachers. In

1934, Hillyer received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his book entitled

Collected Verse. Dorothy and Robert divorced in 1943. In 1948,

Dorothy married Giorgio de Santillana. Dorothy's son, Stanley Hancock

Hillyer, was born on 20 May 1927; he graduated from MIT in 1950. Stanley

Hillyer, an executive with the Raytheon Corporation in Waltham,

Massachusetts, died in August 1969 at the age of only 42.

Dorothy de Santillana was a senior editor at

the Boston publishing firm of

Houghton

Mifflin for many years. She had many notable clients including Julia

Child and Garry Wills, among others. Strangely enough, her relationship with

cookbook author, Julia Child (1912-2004), was of sufficient interest that

Dorothy de Santillana is included as a character in the film about Child's

early life entitled:

Julie and Julia

(2009). Her character is played by actress Helen Coxe (see the above

photograph); in the film, Meryl Streep plays Julia Child.

The noted Pulitzer Prize-winning author and

historian, Garry Wills (born 1934), has the following reminiscence

concerning Dorothy:

I ...

got a call from Dorothy de Santillana, an editor at Houghton Mifflin

publishing house in Boston. She ... told me "You have to write a book about

Nixon." I replied that I had now said everything I knew about him - and

besides, I did not think he could win in November. (So much for my political

prescience.) She maintained that what I wrote about America - its conflicted

Cold War liberalism - was what she wanted to hear more of, whether Nixon won

or lost.

I was

not convinced. She said, "Would you at least come up from Baltimore to New

York, and let me go down from Boston, to talk this over?" I did not know

then what I learned later, that Dorothy had a gift for getting the first

book (or the first important one) from writers she set her sights on - she

had edited early books from David Halberstam and Robert Stone. She was

married to the Renaissance historian at MIT, Giorgio de Santillana, and she

had a wide cultural vision, which, at our New York dinner, she fit my

article into. ...

After

taking on the book assignment, I boarded Nixon's campaign plane (a far

bigger deal than the one he was flying in January, when I had first joined

him). ... Dorothy de Santillana read each draft of the book and found me

some extra advances as it grew in bulk. She went to bat for me with other

editors when they tried to kill my title, Nixon Agonistes

- they said no one could pronounce the second word, people would be

intimidated by it, afraid to ask for it in book stores. She pointed out that

two of the most famous poems in the English language were Milton's

Samson Agonistes and Eliot's

Sweeney Agonistes. When the book came

out, she arranged for a launch party at Sardi's in New York, and the senior

publishing board came down from Boston for it.

--

Garry Wills, Outside Looking In: Adventures of an Observer

(published 2010).

Bibliography

The following is a partial list of Professor

de Santillana's literary works available in English; other than Hamlet's

Mill, most are now out of print. The complete text of Hamlet's Mill

is currently (April 2011) available online at the

Phoenix and Turtle web site.